Even before the onset of the Famine, the Magherafelt Poor Law Guardians believed that that a fever hospital separate to the main building was needed to prevent serious outbreaks of disease. This was forward thinking and in a number of poor law unions throughout Ireland this was to have disastrous effects when the Famine struck. Backed by the statistics of the dispensary doctors who were treating patients throughout the union.

In September 1843 it was first mooted to the Poor Law Commissioners that a fever hospital should be built in Magherafelt, but this was dismissed on the grounds of cost. Instead, the guardians decided to rent a house close by belonging to John Walsh, with Biddy Walsh as fever nurse put in charge of it. The following year it was decided to build a fever house on the workhouse to accommodate forty patients. Built by Alexander McCormack, it received its first patients on 1 January 1846 as the effects of Famine were taking hold. Overseen by Dr. John Vesey as its medical officer, remarkably a former ‘inmate’, Elizabeth Butler, was appointed as the lead nurse in the hospital at £15 a year.

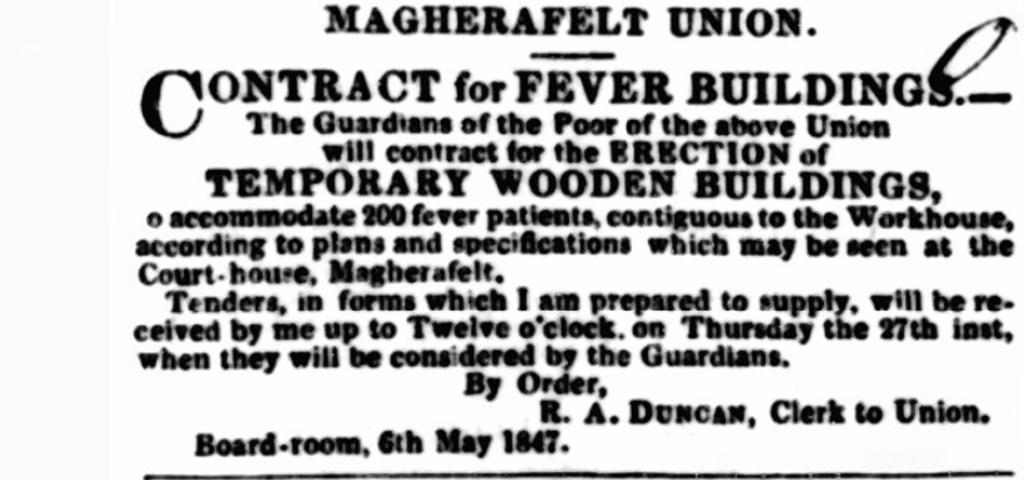

While McCormack’s new build housed fever victims in 1846 there were others who kept in temporary buildings on the grounds which were said to be ‘so fragile that they were blown down by a strong wind’ and the guardians were unable to get tents to replace them’. The growing pangs of hunger in the locality meant that more people quickly succumbed to illness and it was little wonder that an ‘ ambulance’ or workhouse cart for the conveyance of patients to the fever hospital was provided by a James Cassidy, of Maghera, for the sum of £18.

Perusing the ‘Indoor Register’ for this period of Famine, more than 6o% of people entering the workhouse had already contacted some disease or other, while more would do so within the walls of the workhouse.

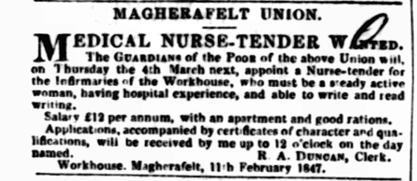

1847, known as ‘Black 47’ for a number of reasons also saw a significant rise in the outbreak of disease within the workhouse as the feeble and hungry were huddled into the main building and the temporary huts. A new team of officials were quickly appointed to help their ill colleagues and included Dr. Burke as temporary medical officer; James McCullough as temporary assistant master, and Bridget Conway as temporary fever nurse. By the spring of 1847 disease had spread through the buildings with rapidity. By early April there were 317 cases in the house, quickly rising to 400. It was during this time that a number of workhouse officials fell ill with fever, so prevalent was it In the buildings. They included even a number of the workhouse officials who fell victim to the disease including the medical officer, Dr. Vesey, the schoolmistress, assistant master, infirmary and fever nurses.

During this worsening time the master, Robert Carse, and the fever nurse, Miss Butler died. Worried by the continued rise in number within the house, the Poor-Law Commissioners sent a Dr. Whistler to meet with the guardians. The outcome was that two large sheds, 100 feet long, were built by John Brown and Co, Belfast, at a cost of £695. This building replaced the earlier structures put up by Richard Donnelly, of Magherafelt, which consisted of two wooden sheds each 80 feet long — one alongside the male and the other alongside the female yard walls, at a cost of £134 18s. Erected within be six weeks, these sheds were filled in a very short time.

By January 1849 although the number of ‘inmates’ (574) was well below the capacity of the workhouse, illness threatened to overrun the building. Dr. Vesey reported that there were 99 cases in the fever hospital and sheds — 7 being affected with fever. There were also 73 in the infirmary, and dysentery and diarrhoea, with English cholera, prevailed to a great extent — there being 45 eases. Whooping cough had also appeared, and he advised that buttermilk and treacle, which were given to the ‘inmates’, should be discontinued and instead new milk given to patients. Vesey also directed that the male and female adults were to be taken out a separate time outside the grounds for hour long walks, something which was later replicated with the workhouse school children.

The Famine conditions also gave rise to trouble in the workhouse as Famine conditions worsened.Insubordination in the house at this time rose as the guardians struggled to cope with the growing numbers and lawlessness. They quickly found the answer though and those found guilty of unruly behaviour were ordered to break stones. In many Irish workhouses, such was their numbers, women were often guilty of such behaviour and in Magherafelt it was no different. There were a number of strict rules to be obeyed for ‘inmates’ and included:

As the numbers increased there were 900 residents by February 1847 and during the worst months of the Famine the guardians appointed James Bell of Luney as an assistant master to cope with the conditions. Reports from the workhouse at this time are somewhat conflicting however, and while the appointment of Bell suggested a greater administrative burden on the staff, reports to government suggested otherwise. In one early 1847 report it was stated that there was ‘no pressure in the workhouse at present, but a special meeting is convened for 4 February to provide additional workhouse accommodation’. There were at that time 775 people in the workhouse, somewhat short of the 900 it was built for, but it was rapidly rising – it had been 228 the previous year at the same time.

Despite these contradictions, the guardians met more frequently during the 1847 (on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays each week) where most of their workload related to people seeking admission with petitions pouring in from every locality in the union. For example, for the week ended 18 February 1847 there were 118 people admitted, and 175 persons were refused admission. The refusal to admit people largely fell to local guardians who oversaw lists at these meetings. Despite the fact that many people were refused entry as they did not ‘qualify’ for admittance, the numbers in the workhouse continued to rise steadily. By the end of February 1847 there were 1,014 inmates, while another 126 were refused admission.

The failure to collect rates from the ratepayers throughout the union had a detrimental effect on the upkeep of the workhouse. As a cost cutting measure the guardians decided to cook the bread consumed by the ‘inmates’ in the workhouse such was spiralling costs. John Wilson of Magherafelt was appointed baker on 7 January 1847 and the flour brought from Muckamore and Coalisland mills. This system continued until after the Famine time numbers had decreased in workhouse.